Leading Sioux Falls’ newest billion-dollar company, CEO’s story blends family roots with futuristic thinking

Jan. 22, 2018

It was a big goal, and not one Tyler Haahr said out loud.

But he met it earlier this month, as his company Meta Financial Group reached a market capitalization of $1 billion.

“It’s pretty exciting,” he said, as the company stock price, which trades appropriately under the ticker symbol CASH on Nasdaq, jumped to a 52-week high of more than $105 per share.

It followed news that Meta was making another big acquisition. This one, a deal to buy Michigan-based Crestmark Bancorp Inc., is positioned to help Meta grow in new ways, combining Crestmark’s commercial lending with Meta’s strong deposits and capital capacity in a deal one analyst called “a marriage made in heaven.”

“We seem to find something new to do every year, whether it’s an acquisition or new products and solutions, and our share price has had a pretty good jump,” Haahr said.

He said it casually, but growth for Meta has been an ongoing, strategic plan. Becoming a billion-dollar company doesn’t generally happen by accident.

“That’s been an internal, personal goal,” Haarh acknowledged. “It’s a big, nice, round number.”

It’s also about to get bigger. Assuming the Crestmark acquisition closes next quarter, Meta’s market cap will be more like $1.5 billion. Even more impressive? Five years ago, it was $90 million.

“It’s been remarkable,” said Doug Hajek, an attorney with Davenport, Evans, Hurwitz & Smith, who joined Meta’s board in late 2013.

“The growth has been dramatic. And they’re very forward-thinking. Tyler has a great vision for the bank, and he’s been doing a great job of executing on that.”

Third-generation leader

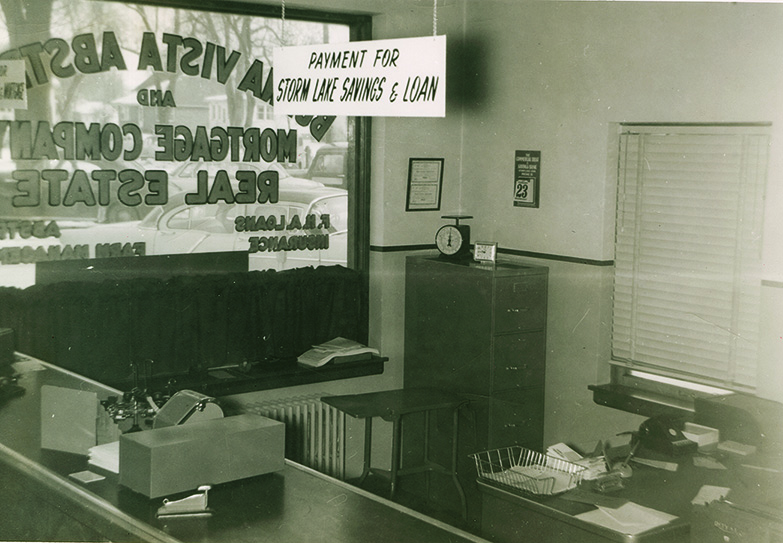

Meta’s roots are in Storm Lake, Iowa, where Haahr’s grandfather, Stan, founded it in 1954. A former high school principal, he started a title company and, with $10,000 in deposits from friends on Main Street, secured a bank charter.

“He basically had a vault and an office in the back of the title company,” Haahr said. “The total size of the total company would be about twice as big as my office,” he continued, looking around his relatively modest space at Meta’s southwest Sioux Falls headquarters.

Storm Lake Savings & Loan branched into other Iowa towns during the 1970s. Haahr’s father, James, took over after starting there in college. At the time, there were a handful of employees.

Tyler and his two sisters spent time in the bank while growing up, including one Saturday morning that involved an accidental alarm pull, prompting police to arrive, “guns pulled, making sure the bank wasn’t getting robbed.”

In eighth grade, though, Haahr wrote a school paper on becoming a lawyer. His mother’s father, Lem Overpeck, was a lawyer who became South Dakota’s attorney general and lieutenant governor.

“So I had a lawyer on one side and business on the other,” he said. “I was going to be a business attorney, a deal guy. That was my goal.”

His parents had met while at USD, and Haahr went on to earn his accounting degree there before going to law school at Georgetown University.

He graduated in 1989 and moved to Arizona, joining the large firm Lewis & Roca LLP, where he jokes he “practiced law with 150 of my closest friends” and represented clients including major hospitals and the Phoenix Suns. He made partner in 1995.

About the same time, back in northwest Iowa, the bank went public. It expanded to Brookings and was in the process of buying two banks in the Des Moines area when an executive vice president position opened. Haahr, who met his wife, Michelle, at USD, had two kids and would leave home before 6:30 a.m. to work in downtown Phoenix.

He knew if he wanted to have breakfast with his family, be at the kids’ activities and coach them in sports, he’d have to make a change.

“I liked being a lawyer. I could have done that my whole career and been happy,” he said. “But it was a good opportunity with the bank and a lifestyle opportunity at the same time.”

They moved back in 1997 and lived in Storm Lake until 2000, when Meta expanded to Sioux Falls and a new phase of growth began.

Meta takes off

Meta’s first physical location in Sioux Falls came in 2000 — on wheels.

“I always call it our mobile facility because I don’t want to call it a trailer,” Haahr said. “But it was a trailer.”

With the trailer sitting on a lot at 33rd Street and Minnesota Avenue while the branch was built there, the Sioux Falls expansion made sense, he said. The bank was in Brookings and had already moved into Des Moines. “And we had connections here, and the city was doing really well,” he said.

Industry veteran Kathy Thorson was hired in 2001 by then-president Tony Trussell to help lead commercial lending.

“I loved the idea that I could help build something from pretty much the ground up,” she said. “We’d literally get in a room around a table and make the lending decisions.”

While she never met Haahr when interviewing, she arrived to her job to find a Post-It note on her desk that said: “So glad you are here. Excited to meet you.”

“My first impressions of Tyler were a little bit larger than life,” she recalls. “They’re this little bank from Storm Lake that moved to Sioux Falls and had pretty exciting projections for growth.”

Almost two decades later, the Sioux Falls market “is by far our biggest for retail banking,” Haahr said, with $600 million in assets and a niche in commercial lending.

The actual Meta name didn’t come until 2004, about the time Meta Payment Systems launched. “Meta” is Latin for “change,” so Meta Financial means “financial change.” The payments division symbolized that, bringing Meta into the “fintech” space before most, if any, knew the phrase.

“If we were going to do business on a national basis with a unique business model, MetaBank made a lot more sense as a very unique name,” Haahr said.

Meta Payments was the division that set the company apart in the marketplace. Its roots are in BankFirst, which also has a location in Sioux Falls now under The Bancorp name, where Brad Hanson started the business line. The company was being sold, and the payments group “wanted to control their own destiny and were going to talk to a handful of banks and private equity companies,” Haahr said.

Most people believe Haahr and Hanson connected for the deal because they happened to be neighbors, Haahr said. In reality, a member of Hanson’s team and a member of Haahr’s team coordinated the meeting that started it.

“Brad walked in my office, and we started laughing,” Haahr said. “We talked for several hours, very straightforward and honest and spent some time doing due diligence.”

In less than a month, the deal was done. An eight-person team moved into MetaBank’s boardroom working around a table and later worked out of the Zeal Center for Entrepreneurship.

“We built everything from scratch. It was a big bet at the time,” Haahr said.

Building the systems to support the prepaid card business, signing up partners for it, doing marketing and compliance, and creating the systems and infrastructure cost tens of millions of dollars. The business plan called for a loss of $1 million to $2 million in the first year before breaking even at 18 months and earning back the initial loss at the end of the third year.

“Things went so rapidly we actually lost $2 million the first year, and we earned it all back before the end of the second year,” Haahr said. “So it was a big bet that obviously paid off.”

Because he was an accounting major and an attorney, “people’s natural assumption is I’m the most conservative guy in the world,” he added. “I’m really the analytical guy who says if the upside is big enough and I can control the downside risk, I’m willing to take a chance and look at new opportunities. And I still am.”

Joel Comer, a principal at New York City-based Sandler O’Neill & Partners LLP, met Haahr more than two decades ago while working with his father.

“He’s absolutely without question exceptional, principled with high, high integrity,” Comer said. “He is exceptionally bright in evaluation and getting intuitive evaluations without having to spend a lot of time on a computer to do so. He’s always been this way, ever since I’ve known him. He just asks very relevant questions in whatever is being discussed and is very thoughtful in his approach to his business and thinks holistically for the company.”

The five-year growth rate for Meta Payment Systems continues to be almost 25 percent annually. Last year, the balance sheet grew more than 30 percent. It has led to relationships with more niche-related businesses that have synergy with the prepaid division, including working with tax preparers to offer refund advances.

“I thought very strongly it was going to go well and be very successful, but it’s gone even beyond my high expectations and wildest dreams,” Haahr said.

Big-picture leader

Many CEOs of publicly traded financial companies the size of Meta arrive on a private aircraft with a small entourage to investor and analyst meetings.

Haahr flies commercial, on his own, and meets one-on-one with investors such as Jordan Hymowitz, managing partner with Philadelphia Financial Fund, a decade-long investor and one of the first large funds to invest in the company.

“Over the years, I got to know the company and became very impressed he was targeting niche areas most banking wasn’t allowed to do because they were over $10 billion. Really, they had the market to themselves for a while, and I thought he made a tremendous amount of very prudent decisions … and executed very well. And it’s not just him. He’s got a very good team around him, and all the payments people are highly thought of in the business.”

Haahr is methodical, logical and “the first person to give credit,” Hymowitz added.

“I think Tyler is very strategically focused and not looking to build an empire, which is why I like him. He’s turned down a number of deals.”

There are few major players in the prepaid business, which is unlikely to change given the high cost of building out the systems to support it, those in the industry say. That, combined with Meta’s proven agility, should bode well.

“They are so embedded in their practice, especially the payment space and specialty finance space … and their management team seems to work extraordinarily well in running things down if they make sense and getting to a ‘no’ fast if they don’t,” Comer said. “Those companies that can get to a ‘no’ quickly often are the ones who can capitalize on really attractive situations. I just think there’s tremendous upside for this company still … in terms of them being able to operate efficiently and really grow this franchise. It’s a great space they’re in, and they do it very, very well.”

Despite traveling about half of his schedule meeting with investors, analysts, regulators and business partners, Haahr remains closely connected to his growing staff, which will top 1,200 this year. Earnings will come out at 7:59 a.m. “and six minutes later, we’re having an all-employee meeting with him sharing what just got realized, why it’s important and what we should look for,” Thorson said.

“Then he’ll say, ‘These are the blocks I’ve allocated to have meetings with employees, so if you want to visit with me one-on-one, I’m available.’ We all just go, ‘Oh my gosh, I can’t believe he’s doing that.’ ”

Haahr, though, is energized by telling the Meta story. It’s one others are starting to tell, too. Last year, Meta was the only company in a 14-state region to make the Fortune 100 list of the fastest-growing companies in the country based on revenue growth, income growth and shareholder return over the past three years. It also was the fastest-growing bank in the country in 2016, according to Bank Director magazine.

“When you’re doing fintech things and having the growth rates we’ve had, highest shareholder returns and highest revenue growth, those are things traditionally done by companies on the coasts,” Haahr said. “But I think just like Sioux Falls is the No. 1 place to do business and has gained respect over the years, I think Meta has as well.”

Haahr can quote earnings and percentage growth for the company’s past eight quarters, “but he can also really dive in and think about potential growth, which is rare,” Thorson said. “Most leaders are real big picture but don’t drill down on the numbers. He can do both.”

He is not a micromanager, she emphasized.

“He’s almost always available if I need something, but he just doesn’t check up on you. If you’ve proven yourself, you’re given the flexibility to run your area.”

Meta employees Colleen Feistner, Ryan Sturm and Rodney Heetland with Tyler Haahr

Haahr has surrounded himself with people of different backgrounds and skill sets, including a percentage of female leadership that contrasts most financial services companies.

“I’m not trying to hire everybody who’s exactly like me. That’s not the best way to grow a business,” he said. “It’s to get people with different backgrounds and different perspectives.”

During his occasional downtime, Haahr indulges his love of sports. He likes to golf and calls himself “a huge NBA fan.” He’s also a music lover and a frequent concertgoer.

As a leader, he describes himself as “very straightforward.”

“I always tell people I work with or who work with me they will always know where they stand. I’ll tell them whether it’s good or bad or somewhere in between. My most important job is to hire good people and help them be successful. I feel like I work for them as much as they work for me or the company.”

At the same time, “our responsibility is to do what’s right for the company, including the shareholders, customers and the employees,” he added.

It’s a balance, he acknowledged.

“But I’m having a blast.”