Jodi’s Journal: Health care’s mixed-message math problem

Nov. 6, 2022

I haven’t done the best job covering one of the biggest business stories bubbling beneath – and sometimes to – the surface of this community.

But I’m going to try today.

The collision of financial factors hitting the health care industry is significant. It’s not clear when or how it all will end, and the potential implications on this community need to be recognized. It’s also an evolving and complex landscape, which can make it tough to capture in any one news story or even series of them.

But let’s start here. Pre-pandemic, most health systems made a 1 percent to 3 percent margin in any given year. It inflated some with an infusion of help from the federal government during the worst of the pandemic, but those dollars are gone.

Now, health systems are experiencing a 25 percent to 40 percent inflationary increase in expenses year over year, year to date.

“There’s probably three components here: medical equipment, medical supplies, and then the biggest is staffing,” said Tim Rave, president of the South Dakota Association of Healthcare Organizations.

“The math doesn’t work. That really right there boils down exactly what is going on.”

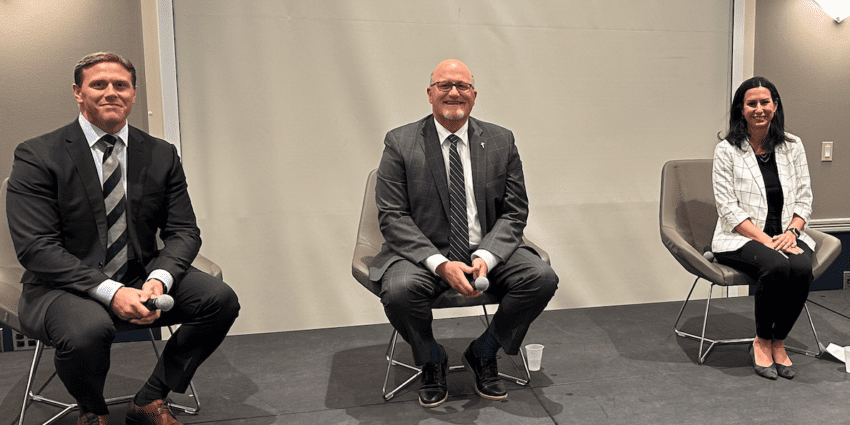

I was fortunate recently to moderate a discussion for the Sioux Falls Development Foundation that included the CEOs of both health systems – Bill Gassen of Sanford Health and Bob Sutton of Avera Health – along with First Premier Bank CEO Dana Dykhouse.

The focus of the event was workforce development, and the conversation included, among other things, some candid discussion of the situation health care is facing.

You can watch much of it for yourself here – the audio kicks in at 3:58.

“Workforce permeates almost every decision that we are making strategically,” Sutton said. “I would tell you (it’s) the No. 1 priority, without question, right now.”

Here is the irony that’s essential to grasp as you seek to understand the landscape: At the same time both systems are holding off on filling some positions, reclassifying some and cutting others, they’re aggressively seeking to hire in areas involving direct patient care.

“On one hand, we are right-sizing an organization from an administrative standpoint, and on the other hand,we are hiring every person we can to take care of people. In the same organization. On the same day,” Sutton said. “And if you think we don’t think that’s a mixed message, you’d be wrong. And we struggle with it as leaders too.”

For instance, Gassen recently sent an all-employee email in which he addressed Sanford will be “closing out programs outside our core mission and reducing administrative expenses.”

At the same time, he shared that the system has 6,000 open positions.

“We do have a unique convergence of some challenges that are happening right now,” he said on the panel. “The difficulty around that messaging is particularly challenging because it’s very very true that … we’re absolutely hiring 6,000 people. We need 6,000 people. We probably need more than 6,000 people today, and those are largely in patient-facing areas.”

People, though, come with a lot of costs. At least half of a hospital’s expenses are personnel related.

Now, remember the multiple times during the pandemic when we reported both health systems making unprecedented investments in their people.

Weeks into the start of the pandemic, Sanford Health waived employees’ health insurance contributions for months and gave most of them one-time cash “stability” payments. A year ago, every Avera Health employee received part of a $50 million investment into workforce that include a $17-per-hour minimum wage and pay increases of at least $2 per hour per employee.

To me, this all made sense as a way to retain and reward people whose services were critical. However, that’s only one snapshot of how personnel-related costs shot up. Pay increases don’t go away; instead, they compound year after year.

The biggest drain, though, came from having to pay contract staff – nurses and other support positions who worked for outside agencies and traveled nationwide filling in staffing gaps during the worst of the pandemic. Traveling staff had existed for years, but the usage – and the cost – shot up. It’s not uncommon to pay hundreds of dollars per hour for a traveling nurse. Of course, the nurse doesn’t get to keep the entire amount, but the pay is more than what would be received in a more permanent position.

The usage has gone down, but these staff still are needed. How else do you even come close to filling thousands of open roles without that?

“You’ve still got your temporary staff, which you’re paying a premium for; regular staff see that and want more money,” Rave said. “Having to pay people more is a good thing … but that money has to come from somewhere. That has to be a well-thought-out financial plan. To do that on the fly during the course of the year only triples down on the problem everyone is facing.”

So you start with those personnel costs. Then, you layer on medical equipment and supplies costing more. And the food needed for patients. And the fuel needed for vehicles. And next thing you know, expenses are up 25 percent to 40 percent. But unlike some businesses, health care can’t easily increase the revenue it brings in to try to break even.

“Hospitals can’t pivot in the middle of the year and change their prices,” Rave said. “Those contracts with insurers and Medicare and Medicaid, as payers the government sets those, but they don’t pivot during the course of the year either. So you wait until now when you’re negotiating those agreements, or a month ago, and see what you can do for next year.”

But no one is expecting payments to increase 25 percent. A member of one health system who was on another panel I moderated recently guessed maybe 3 percent. As Rave said, the math just doesn’t work.

This also is not a uniquely South Dakota issue. Not even close.

The Minnesota Hospital Association released new data recently that highlights what it calls “plunging hospital and health system financials that are being exacerbated by the spiking health care staffing crisis.”

With an almost 250 percent one-year increase in job vacancy rates, a 172 percent decline in year-over-year financials for acute care hospitals, “exponentially rising labor and supply costs, and the need to rely on temporary staffing, there is an intense strain on the state’s hospitals and health systems,” the organization said.

“Our hospitals and health systems are committed to being there when Minnesotans need them, and they need help as the perfect storm – the financial effects of the pandemic and the workforce shortage – worsens with every passing day,” said Dr. Rahul Koranne, MHA president and CEO.

The association’s 2022 MHA Workforce Report is based on a statewide analysis of MHA members, which includes Minnesota’s large health systems and small rural hospitals. Data shows:

- The overall job vacancy rate this year is 21 percent, compared with 6 percent in 2021.

- More professionals within health care are opting for a part-time schedule, making it more difficult for hospitals and health systems to meet operational needs. For the first time, more than half – 57 percent – of registered nurses are not working full-time.

- Overall, 44 percent of all hospital employees are less than full time, up from 37 percent in 2016. This trend is higher among select professional groups, including 68 percent of nursing station technicians and 64 percent of certified nursing assistants.

And, at the same time our Sioux Falls health systems are navigating this environment from a personnel standpoint, they’re also continuing to have to plan for future needs. Think solving this financial conundrum is as easy as not building new buildings? It’s not. Population projections and expected demographic needs show we will not have the capacity to care for this growing region without continuing to invest in the projects you see underway today and that I expect – and hope – you might see as soon as next year.

“You need the buildings because you know there’s going to be the volume of people coming in, and everyone wants and needs and expects those services to be there,” Rave agreed. “So you have to build the buildings and then try and staff them to take care of that volume.”

What does this all mean for us as a community? I think there needs to be recognition of the environment health care is faced with and maybe an adjustment of certain expectations. There are many organizations that have benefited enormously from the trickle-down effect and the generosity of having these two large organizations be such an integral part of the community. But to ensure they’re sustainable and able to deliver on their core mission, which is providing care, they likely will have to make adjustments. I would challenge both businesses and nonprofit organizations that receive significant support from the health systems to take a look inward, including at ways to diversify their own client or donor base. And I encourage them to be open to hiring health care workers whose jobs might have been disrupted as they look for new opportunities and bring with them sought-after skills.

I have no doubt there will be health systems that do not come out of this economic period looking at all like they did when they entered it. There will be mergers and even closures. It already has started nationally. It’s critical that Sioux Falls remain the strong locally based health care hub that has helped define our economy for the past two decades or more. Whatever combination of public and private support, adjustment and innovation it takes to get there will be worth it.