EROS at 50: Managing the changing landscape of our planet

Aug. 28, 2023

By Steve Young, for SiouxFalls.Business

Note: Steve Young worked in communications for EROS from February 2016 to December 2020.

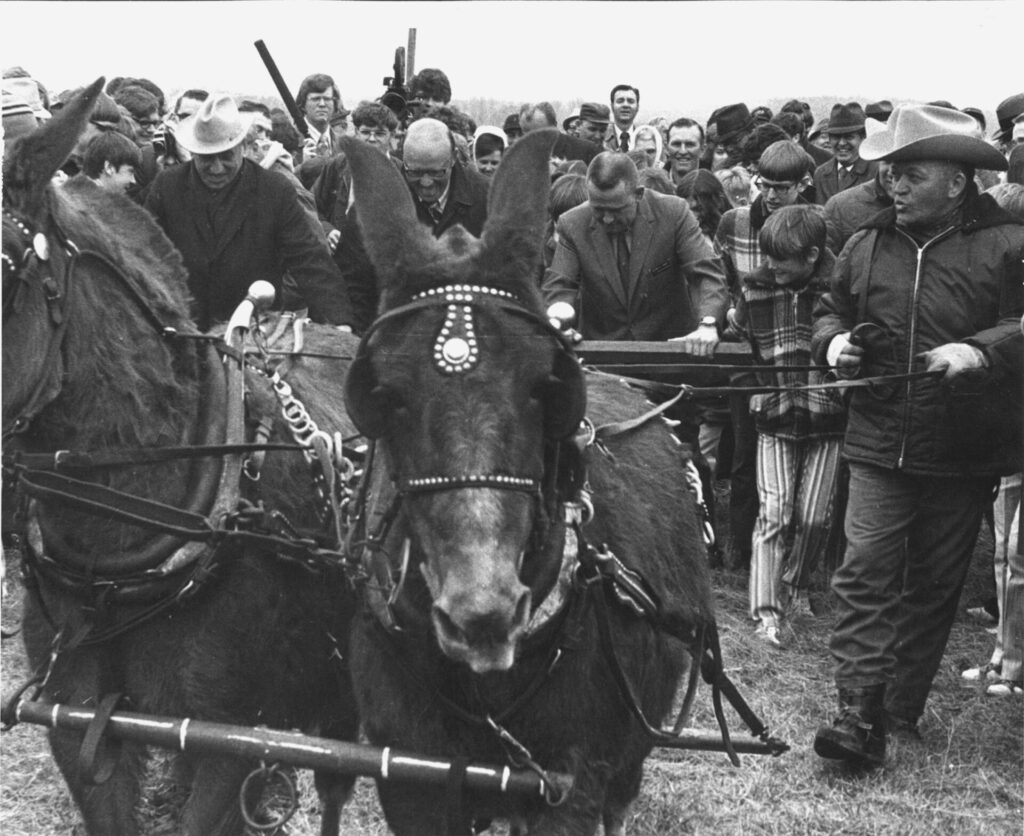

It began with a team of mules, with the aged and splintered handles of an old plow and with a patch of pioneer farmland destined to join the Space Age.

Dignitaries locally and from across the country had gathered 16 miles northeast of Sioux Falls on a cold April day in 1972 for what a government scientist named William Fischer called the “largest Earth scientific experiment ever undertaken by man and possibly the most significant.”

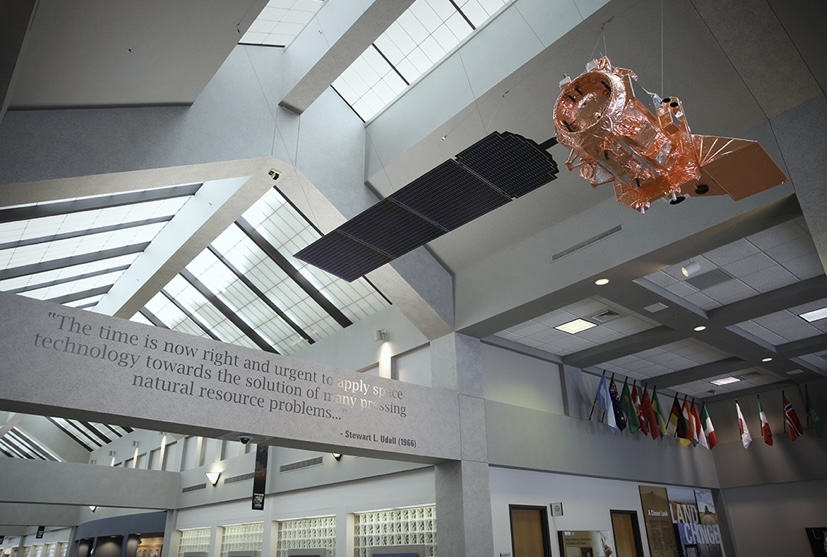

What they had come to do was construct a facility to handle and distribute Earth-observing Landsat satellite data – information that would chronicle and eventually help manage the changing landscapes of our planet. In a nod to America’s ancestral spirit, the first soil was turned by mules and a plow, just as it had been on this same land a century earlier. Within 16 months – in fact, it was exactly 50 years ago this month – that same entrepreneurial spirit yielded what the world now calls the Earth Resources Observation and Science Center, or EROS.

And in so doing, changed the landscape and future of Sioux Falls and South Dakota forever.

Until then, Sioux Falls was a meatpacking town, steeped in the workforce traditions of John Morrell & Co. The arrival of EROS brought about change. A global scientific community eager to obtain spaceborne images of their respective homelands began showing up even before EROS opened its doors. Thirty-three researchers from around the world came to Sioux Falls for the first international training course in June 1973 to learn how to read satellite imagery, and they kept coming well into the late 1980s.

Officials from state and federal agencies began to flock to EROS as well for training and data. And more than that, scientists and engineers recruited from the University of California, Berkeley and across the country began moving to the Sioux Falls area to live, work and raise their families – oftentimes bringing international cultures and customs with them.

And they’re still coming.

“I think … the ability to bring EROS here kind of showed people that this area of the country, specifically Sioux Falls, could really bring in some high-tech type of enterprises,” said Bob Mundt, president and CEO of the Sioux Falls Development Foundation. “I think it was actually the start of … the recruitment of banking and more diverse industries to Sioux Falls than just the ag industries.”

The right geography

EROS came to southeastern South Dakota after the U.S. government decided in 1966 that it intended to launch a satellite to monitor the Earth’s surface. In so doing, it needed a place to store and distribute all that data. It also needed to be located where it could receive transmissions directly from a satellite passing over any part of the conterminous United States – preferably a rural site to avoid radio and TV interference. That limited the location to an elliptical area that stretched from Topeka, Kansas, to just north of Sioux Falls.

Fortunately, Sioux Falls had the right geography for it. It didn’t hurt either that U.S. Sen. Karl Mundt of South Dakota was a friend of President Richard Nixon at the time. Or that the Sioux Falls Development Foundation offered to give the U.S. Geological Survey 318 acres at no charge.

Over the past half-century, EROS – also known as the Karl E. Mundt Federal Building – has become the repository of data from eight Landsat satellite missions – a ninth one, Landsat 6, never reached orbit because of a fuel system issue.

Since 1972, Landsat has captured millions of images of the Earth’s surface and helped make EROS the largest civilian archives of Earth images in the world. And it’s not just Landsat imagery in the archive. Images from other federal agencies are housed at EROS. It is also the federal repository for millions of aerial photography images before and since the satellite era. Space photography from Apollo to Skylab is kept there. In 1996, EROS received 800,000 declassified spy photo-reconnaissance satellites images collected from 1960 to 1972.

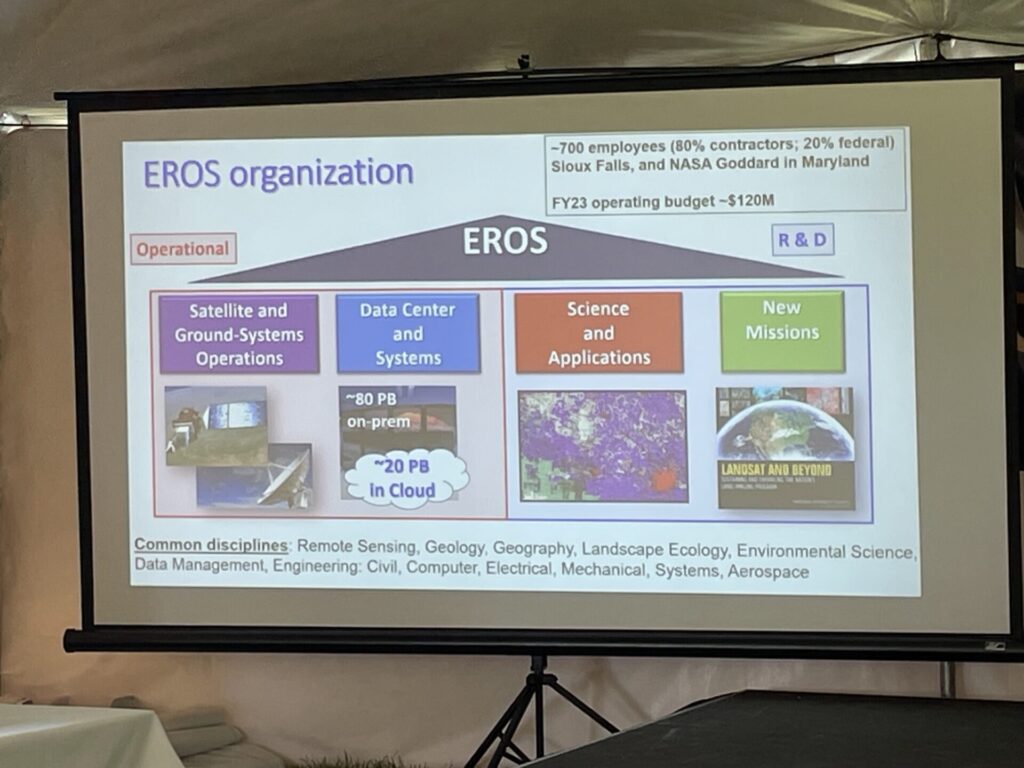

Making that information available and useful for the betterment of the planet has required a diverse and highly educated workforce at EROS — people who could help capture and archive the imagery, and who prepared it to be sent out to users. The facility uses engineers who calibrate images across the different Landsat missions so they all look like they came from the same satellite. And scientists at EROS use the data to study the Earth’s surfaces, how they are changing and how to help protect them.

EROS even manages flight operations for the Landsat satellites still in orbit. Though about 100 EROS employees work at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, operating Landsat’s satellites, there is a backup Landsat Mission Operations Center in South Dakota at EROS.

“We recently tested that ability last December,” EROS director Pete Doucette said. “And what we demonstrated was that we could operate the satellites from here.”

When the USGS decided to stop charging for Landsat data in 2008, the science and applications for all that imagery exploded, especially as other government agencies were pushed to open up their data as well. Every five years, USGS in collaboration with NASA names and finances what it calls the Landsat Science Team — comprised of scientists and engineers, external scientists and application specialists representing industry and university research initiatives – to turn all that free data into innovation and to advise the USGS and NASA on the needs for future missions.

“Developing the capability to monitor change through time and then interrogate that change in such a way to hopefully understand why the change occurred … a number of things came together to make that happen,” Doucette said. “The free and open data policy is one. And computing power is so much greater today. The Landsat Science Team has been a leader in that realm too. Tom Loveland at EROS was the visionary for that team, along with Dr. Jim Irons at NASA.”

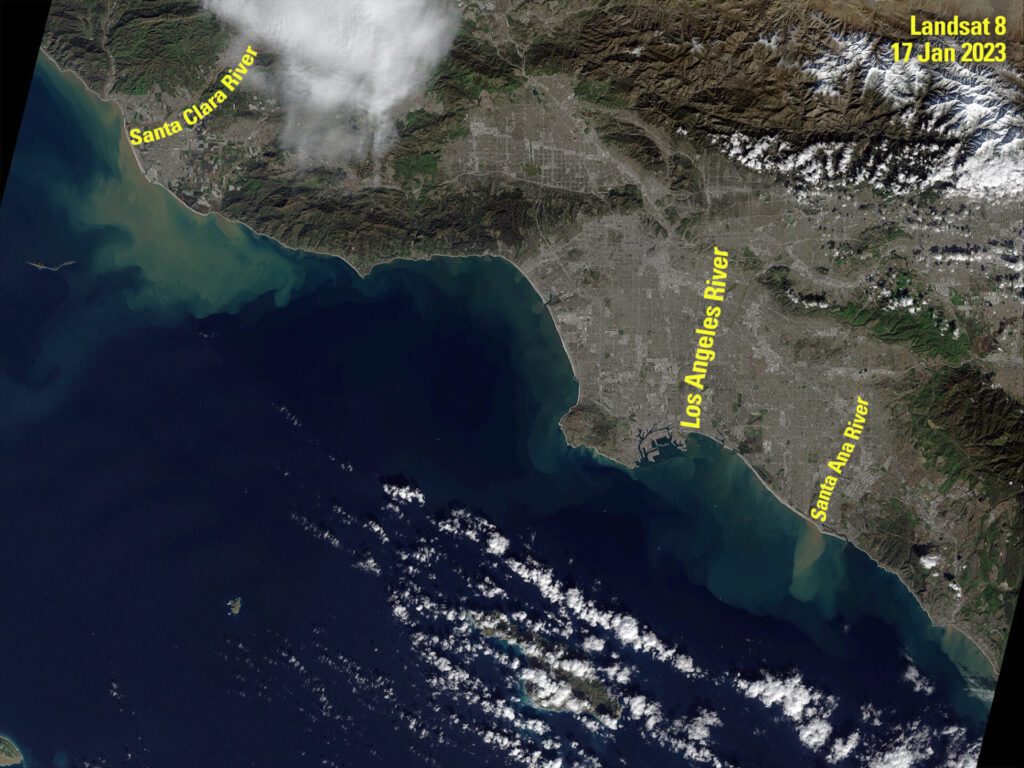

This image taken by Landsat 8 in January shows sediment plumes along the coast of California from rivers and creeks after nine rainstorms occurred in a six-week span following three years of drought.

With images of Earth’s surface going back 50 years, researchers and scientists at EROS – and across the globe – access that data to do time-series studies of vegetation types; tree canopies; wildlife habitats; urban growth; snowpack for water supply or flood potential; damage from fire, volcano and storms; irrigation potential; climate effects; global environmental change; shoreline erosion; and even sea level change.

Here in South Dakota, Landsat data reveal subtle changes in cropland caused by drought, disease or infestations, “the kind of information that you want to provide to farmers so they can have some sense of how things are changing and how they might be able to possibly mitigate any deleterious effects to crops,” Doucette said. “That’s probably the most immediate way to think of what EROS can do for our local economy.”

But there’s more. The data can help resolve ownership issues when lakes flood and swallow up farmland. Insurance adjusters wanting to check the veracity of crop damage claims in South Dakota will turn to satellite data. It even has been used to identify the extent of pine bark beetle infestations in the Black Hills and wildland fire damage there as well.

In Sioux Falls, indeed across the country, applications like Google Maps are at our fingertips today because companies like Google are able to ingest every image in the EROS archive.

Economic impact and more

In fact, so great is the value of the Landsat program that its use for data, research and applications has been estimated to have a $3.45 billion impact worldwide and $2.06 billion in the United States.

EROS and its operations similarly have had significant impacts on the local economy. With 600 employees working out of its rural Sioux Falls site, EROS has operated with a $120 million operating budget in fiscal 2023. Forty years earlier, in 1983, then-director Al Watkins estimated a total local payroll of roughly $10 million annually. With yearly expenditures of $2 million for supplies and utilities back then and approximately $2 million in spending by roughly 3,000 to 5,000 visitors to EROS each year, he estimated the rollover impact of those dollars in the local economy to be $42 million.

And that was 40 years ago.

Thirty years later, in 2015, EROS officials indicated their annual payroll was approximately $60 million and that it had a $500 million economic impact on Sioux Falls over the previous 25 years.

Beyond the dollars and cents, Mundt from the Development Foundation believes EROS has had more than just an economic impact on the region.

“I think EROS was actually kind of the start of that, you know, recruitment of banking and recruitment of more diverse industries than just the ag industries,” Mundt said.

While it’s hard to say how Sioux Falls might look today without EROS, “I think there’s a possibility that certainly we wouldn’t have some of the tech industry that we have here,” Mundt said.

“Maybe Raven and some of the others wouldn’t have necessarily seen us as a place they want to be. Raven has been here a long time, too, but I think their business has flourished because they kind of deal in that aerospace arena. Both they and POET are doing so many things on the cutting edge of technology when it comes to using satellite imaging.”

From the perspective of education, EROS’ arrival provided incentives to institutions like South Dakota State University, Dakota State University, South Dakota School of Mines & Technology and others to develop programming necessary to meet workforce needs in such areas as information technology, engineering, geography and physical science.

Ed Hogan, who was hired at SDSU to start a geography department more than 50 years ago, was sent to EROS early on by school President Hilton Briggs to foster what he hoped would become a significant collaboration between remote-sensing and geography.

EROS officials told Hogan they needed geographers with master’s degrees. SDSU made that happen. Twenty years ago, EROS and SDSU joined together to create the Geospatial Sciences Center of Excellence on the campus to do research and train doctoral candidates in remote-sensing as engineers and geographers.

By his calculations, Hogan said there were 65 geographers working at EROS when he retired. He doubts he would have been able to say that had EROS been located somewhere else.

“Without EROS, we wouldn’t have the scientific knowledge that it contributes to the world today,” Hogan said. “We would not have the skills for the people who want to stay and work in this state. We wouldn’t have the salaries they earn. And it wouldn’t have had the impact on the school like it has on us.”

Doucette admits that recruiting and retaining a remote-sensing workforce remains a challenge for him and EROS. Of the factors contributing to that, geography is a big one. Aerospace engineers and remote-sensing scientists aren’t streaming into South Dakota, he said. And so, he wants to rekindle conversations with both community leaders in Sioux Falls and statewide university officials, particularly to discuss workforce assistance.

Doucette plans to embark on what he calls a campaign of sorts this fall, going to local and area universities to explain what EROS does and to exchange ideas on building the workforce for the center.

“To be honest, we probably haven’t maintained as regular a relationship as we should have over the years” with the city of Sioux Falls and universities, Doucette said. “Bob Mundt and I have had this discussion a few times over the last few years as to how we might put together some kind of strategy to attract the kind of talent and high-tech skills that EROS does employ. It may require some creative thinking.”

The next 50 years

That’s a conversation Mundt certainly wants to continue, especially as EROS moves on to the possibilities of the next 50 years, with the advent of artificial intelligence, expansive storage and computing in the cloud, and advances in satellite technology that offer the possibility of monitoring land use and land changes on an almost real-time basis from space.

Sioux Falls needs to stay invested in that, Mundt said. It needs to stay cognizant as well of any government conversations that might hint at cutting funding, realigning EROS with other centers across the country or even closing it.

Rapid City went through that conversation in 2005 when the Base Realignment and Closure Commission considered closing Ellsworth Air Force Base. Back then, the Rapid City community rose up and, working hand in hand with South Dakota’s congressional delegation and state officials, kept that base open.

Mundt is convinced the same thing would happen here should EROS be threatened. And it wouldn’t just be Sioux Falls leading the charge, he said. Other communities would join that cause, Mundt believes. The university systems and city halls in places like Brookings and Madison would step up, he said, as would communities and organizations in Minnesota and Iowa.

“I think we would absolutely do that … in a heartbeat,” he said of rallying to secure EROS’ future in this area. “In all honesty, it could reach as far as Rapid City. When they were looking at the Ellsworth shutdown, my understanding was Sioux Falls signed a petition to make that not happen too.

This tree was just planted at EROS to recognize Thomas Loveland, long-time chief scientist at the center and the visionary for the Landsat Science Team, which provides scientific and technical evaluations to help ensure the continued success of the Landsat program. A conference room at EROS was named after Loveland during the center’s 50th anniversary celebration earlier this month. Loveland died May 13, 2022.

“So I think all of South Dakota realizes what EROS means, just as we realized what Ellsworth Air Force Base means. We would work just as hard as we can to make sure that doesn’t happen.”

The hope, he and Doucette agree – whether today or another 50 years into the future – is that they’ll never have to.